The Story Of TheTomb Of The Unknown Warrior

Contents

- The Reverend David Railton

- The Selection of the Body at Saint-Pol

- Escort From Saint-Pol To The Citadelle At Boulogne

- The Casket

- To the Port of Boulogne

- Boarding HMS Verdun

- Arrival at Dover

- By Train to London Victoria

- The Procession to Westminster Abbey

- The Ceremony

- the Laying in State

- The Inscription on the Marble Stone

- Postscript

The tomb of The Unknown Warrior, who was buried in Westminster Abbey, London on 11 November 1920, holds an unidentified British soldier killed during the First World War on the Western Front. The battle field that the Warrior came from is not publicly known, and has been kept secret so that the Unknown Warrior might serve as a symbol for all of the unknown dead wherever they fell.

The germ of the idea of a Tomb of the Unknown Warrior was first conceived in 1916 by an Army chaplain, the Reverend David Railton. While serving on the Western Front in France, he had seen a grave marked by a wooden cross, which bore the hand-written legend ‘An Unknown Soldier of the Black Watch’.

After the war, in 1920, he wrote to the Dean of Westminster with the proposal for a tomb of the unknown warrior. An unidentified British soldier from the battle fields in France should be buried with due ceremony in Westminster Abbey “amongst the kings” to represent the many hundreds of thousands of Empire dead.

The idea was strongly supported by the Dean and the then Prime Minister David Lloyd George. There was initial opposition from King George V (who feared that such a ceremony would reopen the wounds of a recently concluded war in a period of great social tension and strikes) and others, but Railton’s idea eventually won through.

The War Graves Commission was instructed to create the National Site of Mourning to be dedicated on Armistice Day 1920. Arrangements were placed in the hands of Lord Curzon of Kedleston who prepared in committee the details of the service and exact location for what was to be the ‘Tomb of the Unknown Warrior’.

The Selection Of The Body At Saint-Pol

The remains of four soldiers were exhumed from four principal battle fields – The Aisne, Somme, Arras and Ypres (some unconfirmed reports suggested that there were 6 bodies) – and brought to a makeshift army chapel at St Pol near Arras, France on the night of 7 November 1920.

The bearer parties were immediately returned to their units and a guard placed on the door. At midnight Brigadier General L.J. Wyatt (above), the Officer in charge of troops in France and Flanders and Lieutenant Colonel E.A.S. Gell of the Directorate of Graves Registration and Enquiries went into the chapel alone.

The remains were on stretchers, each covered by a Union Flag: the two of officers did not know from which battle field any individual body had come. General Wyatt with closed eyes rested his hand on one of the bodies.

The two of officers placed the body in a plain coffin and sealed it. The other three bodies were reburied. General Wyatt said they were re-buried at the St. Pol cemetery but Lt. (later Major General Sir) Cecil Smith says they were buried beside the Albert-Baupaume road to be discovered there by parties searching for bodies in the area.

Although unknown, it seems highly likely that the bodies were carefully selected and the Unknown Warrior was chosen from the remains of a soldier serving in Britain’s pre-war regular army killed in 1914, making any identification of the body impossible.

Escort From Saint-Pol To The Citadelle At Boulogne

The coffin stayed at the army chapel overnight, and in the morning, Chaplains of the Church of England, the Roman Catholic Church and Non-Conformist churches held a joint service.

The body was then escorted under guard, with troops lining the route on the afternoon of November 8, from St Pol to the medieval castle within the ancient citadel at Boulogne-sur-Mer. For the occasion, the castle library was transformed into a “chappelle ardent” and a company from the French 8th Infantry Regiment recently awarded the Legion d’Honneur, stood watch in vigil overnight.

The Casket

The following morning, two undertakers entered the castle library and placed the coffin into a casket made of the oak timbers of trees from Hampton Court Palace. The casket was banded with iron and a medieval crusader’s sword, chosen by the King personally from the Royal Collection, was fixed to the top and surmounted by an iron shield bearing the inscription ‘A British Warrior who fell in the Great War 1914-1918 for King and Country’.

The Ypres or Padre flag

It was covered with the flag that David Railton had used as an altar cloth during the War (known as the Ypres or Padre’s Flag, which now hangs in St George’s Chapel, Westminster Abbey).

To The Port Of Boulogne

The casket was then placed onto a French military wagon, drawn by six black horses. At 10.30 am, all the church bells of Boulogne tolled; the massed trumpets of the French cavalry and the bugles of the French infantry played Aux Champs (the French equivalent of the “Last Post” at the time). Then, the mile-long procession – led by one thousand local schoolchildren and escorted by a division of French troops – made its way down to the harbour.

Boarding HMS Verdun

At the quayside, on the Quai Carnot Marshal Foch saluted the casket and made a speech before the White Ensign was lowered to half mast. The coffin was then carried up the gangplank of the destroyer, HMS Verdun (L93),and piped aboard with an admiral’s salute. Verdun was selected to carry the Unknown Warrior across the English Channel because her name would be a tribute to the French people and the endurance of their armies at Verdun in 1916.

Arrival At Dover

The coffin was laid on the quarterdeck and covered with wreaths of white flowers, some so large that it took four soldiers to lift one. Shortly before noon, Verdun moved away from the quay as sailors fired a rifle salute along with the big guns of the French forts. An escort of six battleships accompanied Verdun through the mist to Dover where a 19-gun Field Marshal’s salute was fired from Dover Castle. She tied up at Admiralty Pier where General Sir John Longley supervised the six high-ranking officers from the three Armed Services who bore the coffin ashore.

It was landed at Dover Marine Railway Station at the Western Docks on 10 November and was taken ashore to a train by a bearer party of six Warrant Officers from the Royal Navy, the Royal Marines, the Army and the Royal Air Force and escorted by two Generals, two Admirals and two Air Marshalls.

By Train to London Victoria

The coffin then was carried to London in South Eastern and Chatham Railway General Utility Van No.132. This had previously carried the bodies of Edith Cavell and Captain Charles Fryatt, both executed by the Germans, in May and July 1919 respectively. (The van was fully restored in 2010 by the Kent and East Sussex Railway and is now a museum usually kept at Bodiam Station.)

The train continued its journey to Victoria Station, where it arrived at platform 8 at 8.32 pm that evening and remained overnight under escort of the 1st Battalion Grenadier Guards. (A plaque at Victoria Station marks the site and every year on 10th November, a small Remembrance service takes place between platforms 8 and 9.)

The Procession To Westminster Abbey

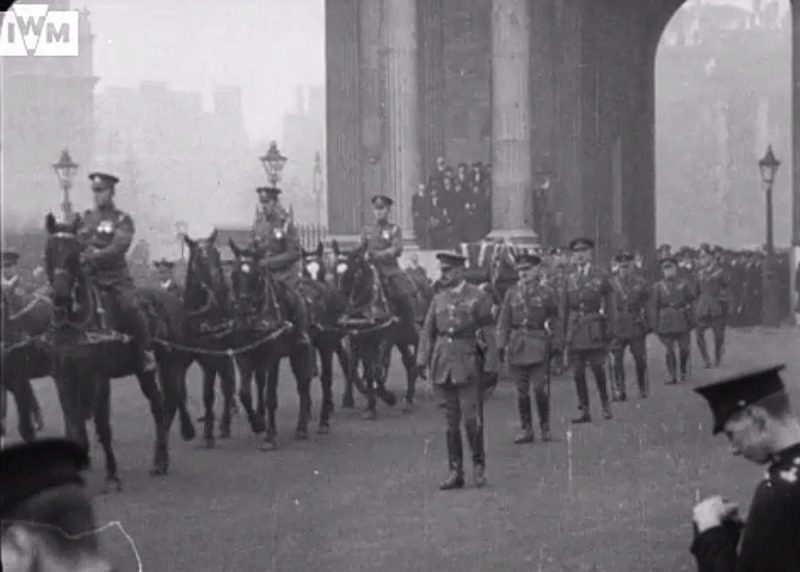

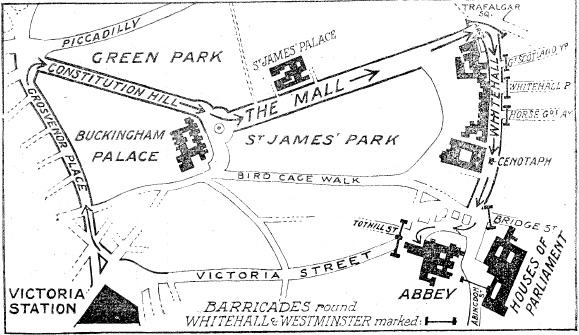

The following morning, 11 November 1920, the casket, covered with the Union Flag, on which was placed a steel helmet and side arms, was placed onto a gun carriage of the Royal Horse Artillery drawn by six horses and led by a Firing Party and the Regimental bands of the Brigade of Guards, set off through immense and silent crowds. As the cortege set off, a further Field Marshal’s salute was held in Hyde Park. The route followed was Hyde Park Corner, The Mall, and to Whitehall where the new Cenotaph, a “symbolic empty tomb”, was unveiled by King-Emperor George V.

(Images courtesy Imperial War Museum)

The Ceremony At The Cenotaph

At the Cenotaph, the carriage halted and King George placed a wreath of roses and bay leaves (the Poppy Appeal did not begin until 1921) on the coffin.

While the Cenotaph unveiling was taking place the Choir inside the Abbey sang, unaccompanied, “O Valiant Hearts” (to the tune Ellers). The hymn “O God our help in ages past” was sung by the congregation and after prayers there was the two minutes silence at 11am.

After the two-minute silence the gun carriage continued to Westminster Abbey followed by the King, the Royal Family and ministers of state.

The Guards Carry The Coffin Into The Abbey

Once outside the Abbey , the coffin was borne by soldiers from the Brigade of Guards into the Abbey, whilst the hymn “Contagion of the Faithful Departed” was sung. The choir processed to the north porch to meet the coffin, with the hymn “Brief life is here our portion” being sung.

The VC Honour Guard photographed before the ceremony

The Ceremony

The shortened form of the Burial Service began with the singing of the verses “I am the resurrection and the life” (set by William Croft) and “Thou knowest Lord” (by Henry Purcell) during the procession to the grave. The coffin was borne to the west end of the nave through the congregation of around 1,000 mourners and a guard of honour of 100 holders of the Victoria Cross (from all three services). They were under the command of Colonel Freyburg VC. The choir sang the 23rd Psalm. My painting of two of the members of this guard, SPO Leach CGM and CSM Doyle MM VC, can be seen here.

The guests of honour were a group of about one hundred women, who had been chosen because they had each lost their husband and all their sons in the war. “Every woman so bereft, who applied for a place got it”.

The VC Honour Guard files into the Abbey

Burial of the Unknown Warrior by Frank O. Salisbury. The painting now hangs in Committee Room 10 in the Houses of Parliament

The King And The Procession By The VC Holders

After the hymn “Lead kindly light,” the King stepped forward and dropped a handful of French earth onto the coffin from a silver shell as it was lowered into the grave. The Victoria Cross holders then led past either side of the grave.

At the close of the service, after the hymn “Abide with me” (tune Eventide) and prayers, the congregation sang Rudyard Kipling’s solemn Recessional “God of our fathers” (to the tune Melita), after which the Reveille was sounded by trumpeters. The Last Post had already been sounded at the Cenotaph unveiling.

The Laying In State

The grave was then covered by a silk funeral pall, which had been presented to the Abbey by the Actors’ Church Union in memory of their fallen comrades, with the Padre’s flag lying over this. Servicemen kept watch at each corner of the grave.

Wreaths brought over on HMS Verdun were added to others around the grave. The Abyssinian cross, presented to the Abbey at the time of the 1902 coronation, stood at the west end. The Abbey organ was played while the church remained open to the public.

After the Abbey had closed for the night some of the choristers went back into the nave and one later wrote “The Abbey was empty save for the guard of honour stiffly to attention, arms (rifles) reversed, heads bowed and quite still – the whole scene illuminated by just four candles.”

The Inscription On The Marble Stone

The coffin was buried under 100 sandbags of soil brought from the battle fields, on 18th November and later covered with a black Belgian marble stone (It is the only tombstone in the Abbey on which it is forbidden to walk) featuring a gilded inscription, composed by Dean Ryle, Dean of Westminster, engraved with brass from melted down wartime ammunition:

BENEATH THIS STONE RESTS THE BODY OF A BRITISH WARRIOR UNKNOWN BY NAME OR RANK BROUGHT FROM FRANCE TO LIE AMONG THE MOST ILLUSTRIOUS OF THE LAND AND BURIED HERE ON ARMISTICE DAY 11 NOV: 1920, IN THE PRESENCE OF HIS MAJESTY KING GEORGE V HIS MINISTERS OF STATE THE CHIEFS OF HIS FORCES AND A VAST CONCOURSE OF THE NATION

THUS ARE COMMEMORATED THE MANY MULTITUDES WHO DURING THE GREAT WAR OF 1914 – 1918 GAVE THE MOST THAT MAN CAN GIVE, LIFE ITSELF, FOR GOD FOR KING AND COUNTRY FOR LOVED ONES HOME AND EMPIRE FOR THE SACRED CAUSE OF JUSTICE AND THE FREEDOM OF THE WORLD

THEY BURIED HIM AMONG THE KINGS BECAUSE HE HAD DONE GOOD TOWARD GOD AND TOWARD HIS HOUSE

Around the main inscription are four texts:

THE LORD KNOWETH THEM THAT ARE HIS (top) UNKNOWN AND YET WELL KNOWN, DYING AND BEHOLD WE LIVE (side) IN CHRIST SHALL ALL BE MADE ALIVE (base) GREATER LOVE HATH NO MAN THAN THIS (side)

The last three lines inscribed on the tomb are taken from the bible (2 Chronicles 24:16): ‘They buried him among the kings, because he had done good toward God and toward his house’.

Postscript

To the surprise of the organizers, in the week after the burial, an estimated 1,250,000 people visited the abbey, filing past the tomb, guarded by four servicemen.

Special permission had been given to make a recording of the service but only the two hymns were of good enough quality to be included on the record, the first electrical recording ever to be sold to the public (with profits going to the Abbey’s restoration fund). You can hear here the recording of Abide With Me and Kipling’s Recessional.